Proposals: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

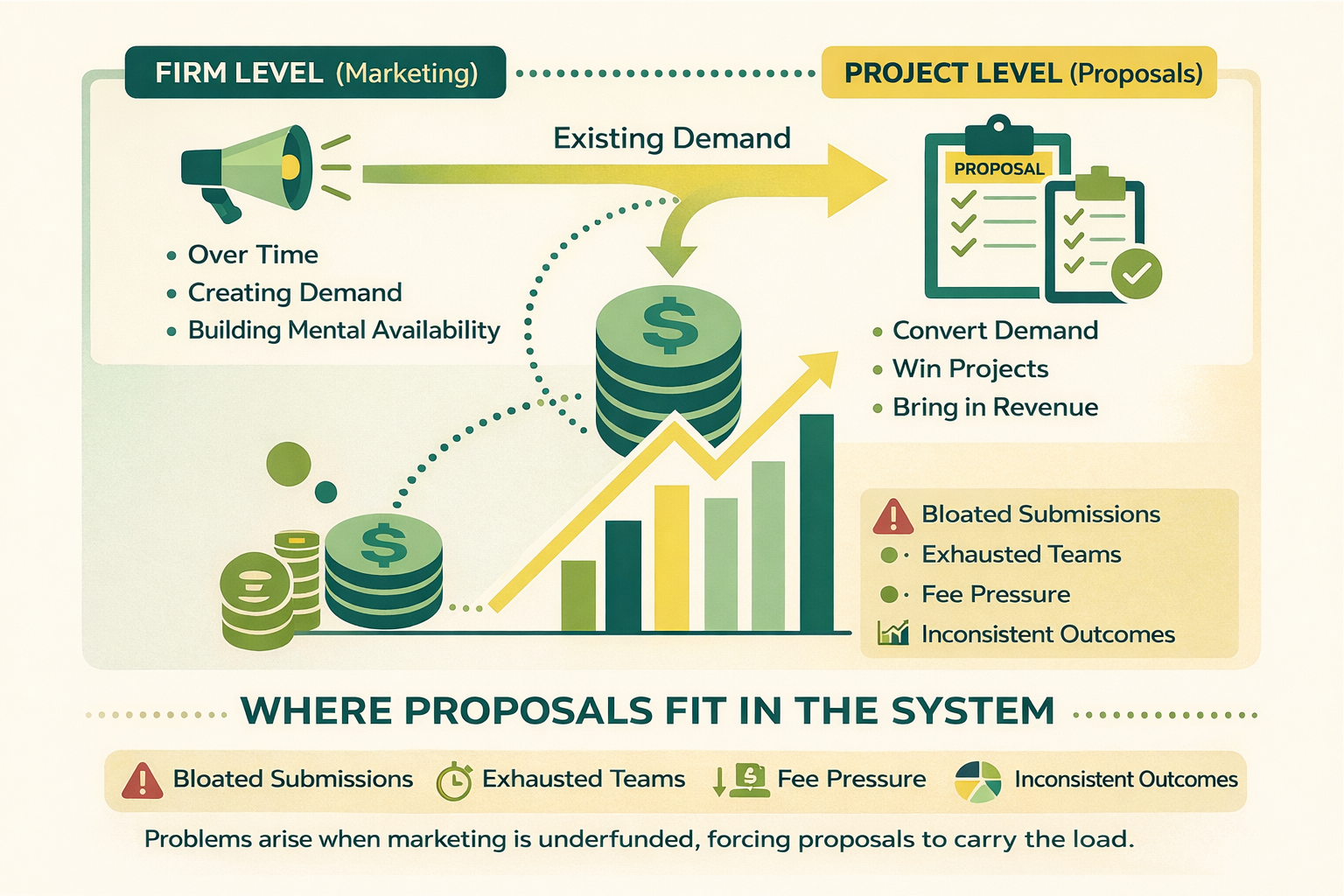

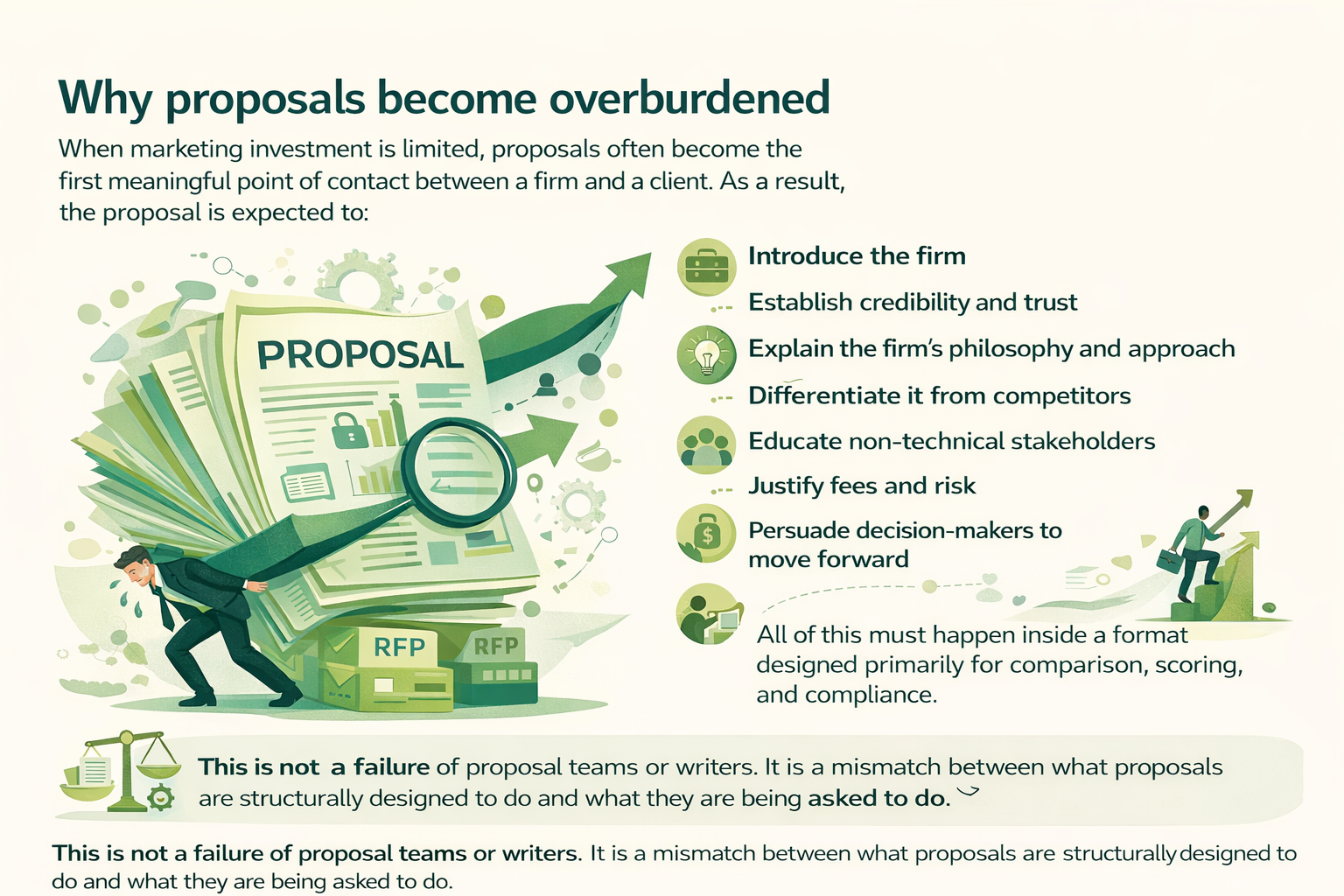

For many architecture and design firms, proposals have long been the primary way work comes into the practice. They account for a significant share of marketing and business development effort and sit at the centre of how expertise is positioned, risk is assessed, and opportunity is converted into revenue.

That central role has not changed. What has changed are the conditions under which proposal work now takes place. Projects are more complex than they once were, procurement structures are more demanding, timelines are tighter, and legal and contractual requirements are heavier. Firms are often managing multiple, overlapping pursuits with limited advance notice. In this environment, proposal work requires far more than technical competence or compliance — it demands judgment, coordination, and systems that can withstand sustained pressure.

In this interview, we spoke with two senior practitioners whose roles sit at the intersection of marketing, business development, and firm leadership: Lindsay Keir, Director of Marketing at II BY IV DESIGN, and Natasha Basacchi, Director of Business Development at Zeidler Architecture. Together, they bring deep, practice-based experience across proposals, positioning, risk management, and growth strategy, shaped by years of working inside large, multi-sector design organizations.

At II BY IV DESIGN, Lindsay leads marketing and business development strategy across hospitality, residential, retail, branded environments, and experiential work. Her role spans brand positioning, market research, and pursuit strategy, with a strong focus on translating creative intent into clear, compelling narratives that align with firm objectives and operational realities.

At Zeidler Architecture, Natasha oversees business development and pursuit strategy across Canada. With a background in architecture and more than a decade at the firm, she brings a holistic perspective across proposals, marketing, and communications — balancing long-term vision with practical execution to support strategic growth and strong client relationships.

This discussion does not question the central role proposals already play in design practices. Instead, it explores how that role can be elevated. Drawing on their experience, Lindsay and Natasha outline the systems, judgment, and structural approaches that distinguish competent proposal execution from practices that are consistently set up to pursue — and win — the right work.

Capacity Planning and Proposal Prioritization

Oomph: Capacity planning is the daily reality of proposal teams. They’re constantly balancing firm strategy, leadership priorities, uneven workloads, very short deadlines, and the coordination of large, multidisciplinary teams — all while being expected to produce high-quality work under pressure. Given those conditions, how do you manage capacity in practical terms, especially when proposal demand is unpredictable?

Natasha Basacchi: Capacity planning is a balancing act, largely because opportunities don’t arrive evenly. One practical approach is looking at historical patterns. Tracking proposal deadlines across multiple years makes it easier to identify busy periods and anticipate where pressure will build.

That planning isn’t limited to the proposal team’s workload. It also affects vacation scheduling and coverage for technical experts and senior staff who will be needed during peak proposal periods. Having a proposal calendar that shows patterns year over year helps teams anticipate pressure points and make more informed staffing decisions.

Oomph: Lindsay, what does that look like from your perspective? What matters most when teams try to forecast capacity?

Lindsay Keir: Having data matters — and it’s also where many firms run into real limitations. One challenge is that proposal work is often tracked under a single business development code, which makes it difficult to understand what proposals actually cost in terms of hours and effort. Without that visibility, planning becomes guesswork.

Even when firms can’t track perfectly, tracking proposals by sector and relationship status can still help with planning — particularly for identifying expected opportunities. Pre-existing client relationships also improve forecasting because firms often have a better sense of what’s coming.

Oomph: That distinction between workload and mix is important.

Natasha Basacchi: Yes — and even basic tracking can help determine when additional support is needed. Large or complex proposals often require more senior involvement, and having that visibility earlier helps teams manage capacity more realistically.

Oomph: Firm size plays a role here as well. What approaches would you suggest for smaller firms that don’t have the same depth of staffing or systems?

Lindsay Keir: For smaller firms, clarity around wins, losses, and debriefs becomes especially important. When resources are limited, leadership needs clear information so effort isn’t spent on poor-fit pursuits.

Natasha Basacchi: Even small firms can gather useful data that helps them understand what works and guides strategic pivots. The key is focusing resources where there’s proven success or a clear opportunity.

Data and Tracking — Turning Experience into Judgement

Oomph: One of the things that’s coming through very clearly is the role data now plays in making all of this manageable — capacity decisions, Go / No-Go calls, and confidence in when to say yes or no. How does data actually get used in proposal management, and what kinds of information make the biggest difference in practice?

Natasha Basacchi: The more information you can track, the more informed your decisions become. For example, tracking how much time different types of proposals take — large infrastructure pursuits versus smaller private-sector opportunities — gives teams a clearer picture of how many complex pursuits they can realistically manage at the same time, and where there’s still capacity for smaller or less resource-intensive work.

Over time, that kind of tracking helps teams understand not just workload, but mix: when they can take on another major pursuit, when they can’t without additional support, and which types of proposals will require deeper senior technical involvement.

Oomph: Lindsay, granular tracking sounds incredibly valuable — but it’s not always easy to implement. How do you see that tension playing out inside firms?

Lindsay Keir: That’s often the reality. From an accounting perspective, many firms prefer to keep proposal work under a single business development code. Opening multiple codes for individual pursuits can complicate accounting, so everything tends to get lumped together.

The downside is that you lose visibility into what different proposals actually cost. Without that baseline, it’s much harder to say, “We can support two major pursuits and several mid-sized ones this quarter,” because you don’t have clear data to work from.

Go / No-Go — Essential, but Rarely Simple

Oomph: Once you start talking about forecasting and capacity, Go / No-Go inevitably comes into the picture. It’s often presented as a clean, mechanical process — fill out the matrix, tally the scores, and the answer becomes clear. In practice, that hasn’t always been my experience. How useful is Go / No-Go, really, when it comes to making good pursuit decisions?

Lindsay Keir: Go / No-Go matrices can be useful, but they’re inherently subjective. Even with a scoring system in place, those scores don’t tell the whole story. Decisions are influenced by factors that don’t fit neatly into a checklist — client relationships, timing, available resources, and where the firm is trying to go strategically.

Because of that, the matrix is usually just one input. What matters more is stepping back and asking broader questions about fit, capacity, and opportunity, rather than relying solely on a numeric result.

Oomph: Natasha, from your perspective, what actually makes a Go / No-Go process work — or not work — inside a firm?

Natasha Basacchi: For Go / No-Go to work well, there needs to be clarity around the process — who is gathering the information, who is weighing in, and how the decision is made. When that structure isn’t clear, decisions can stall and a lot of effort gets spent without a clear direction.

Having a defined process helps ensure the right information is considered at the right time and that teams don’t do significant work before the firm has really committed to pursuing an opportunity.

Oomph: One thing that’s implicit here is the role proposal teams play in these decisions. Because they’re involved across many pursuits, they often see patterns that aren’t visible when you’re focused on a single project. How does that perspective factor into Go / No-Go discussions?

Lindsay Keir: Proposal teams add real value to Go / No-Go conversations. They see trends across sectors, clients, and proposal types, and that perspective strengthens decision-making. It reinforces that proposal teams aren’t just producing documents — they’re contributing judgment that helps firms pursue the right work.

Pre-positioning as Business Development and Intelligence Gathering

Oomph: Let’s talk about pre-positioning. In an ideal world, firms would have advance visibility into what’s coming and fewer surprises when an RFP is issued — but that’s not always the case. From your experience, how does pre-positioning actually work in practice?

Natasha Basacchi: Surprises still happen, but there are usually fewer of them when firms are doing the groundwork in advance — if they have the setup to support it. When that groundwork is in place, the RFP becomes the final step rather than the beginning.

For major projects, teams can often be formed well in advance — sometimes a year or more before an RFP is issued. That early preparation makes a real difference. It gives firms a clearer sense of what’s coming and reduces the scramble when the RFP finally drops.

Lindsay Keir: Pre-positioning also depends on how business development information is shared internally. I’ve always worked with regular BD and marketing check-ins involving leadership and sector leads — however the firm is organized — to review active proposals, what’s coming down the pipeline, new opportunities, and emerging relationships.

Keeping that information visible and current helps firms anticipate work earlier and align proposal planning with broader business development activity, rather than reacting at the last minute.

Proposal Leadership and Infrastructure — Who Owns the Proposal Now?

Oomph: I want to shift into proposal leadership and infrastructure, because this is an area where there’s been a real change over time. Traditionally, in many firms, proposals were written by partners, sector leads, or technical specialists, with marketing teams providing support. Is that still something you see?

Lindsay Keir: No — not in a very long time. Proposal work has become highly specialized. Over time, people working in proposals develop deep expertise in how projects are actually delivered — scheduling, delivery models, risk mitigation — because they’re constantly immersed in these issues across many pursuits.

That experience means proposal teams today are well equipped to draft substantial portions of submissions themselves. Partners still play a critical role, but it’s more about review, refinement, and final approval than writing content from scratch.

Oomph: So ownership has shifted — not away from leadership, but toward a more structured division of roles.

Natasha Basacchi: Exactly. And it’s not just about technical knowledge — it’s also about managing complexity. Proposal teams are coordinating multiple pursuits at once, often under very tight timelines, with input coming from many people across the firm.

That requires continuity and structure. Proposal specialists are responsible for holding the process together — coordinating inputs, managing schedules, and shaping everything into a coherent submission. Technical experts contribute content, but the responsibility for integration and delivery sits with the proposal team.

Oomph: So ownership isn’t just about who writes — it’s about who manages the process end to end.

Lindsay Keir: That’s right. Proposal teams today are doing much more than editing. With access to content libraries and institutional knowledge, they often prepare large portions of proposals — including fee-related sections — with leadership providing oversight and sign-off.

That shift reflects how central proposal teams have become to how firms compete and pursue work effectively.

The Proposal Toolkit — Templates, Systems, and Continuity

Oomph: One of the things that comes through clearly in this conversation is how much proposal work now depends on having the right systems and infrastructure in place. Beyond writing, what actually makes the biggest difference in practice?

Natasha Basacchi: What helps most is having a basic set of tools teams can rely on every time — proposal planning templates, task lists, fee templates, and shared content libraries. When those are in place, teams aren’t reinventing the process with every pursuit and can focus their effort on the work that really matters.

That structure becomes especially important when multiple proposals are underway at once. Clear task lists showing what’s in draft, what’s complete, and who’s responsible help teams stay aligned as deadlines approach. It also creates continuity — if someone becomes unavailable, another person can step in without losing momentum.

Narrative content benefits from the same approach. Instead of relying on a single generic firm profile, content typically lives in libraries organized by sector, project type, or expertise. Teams can start from relevant material and tailor it to the specific client and pursuit.

Oomph: And data plays into that infrastructure as well.

Natasha Basacchi: Yes — but it’s important not to try to capture everything at once. Data can feel overwhelming, so starting with a few core metrics, like win rates and reasons for wins or losses, is often more effective. Even simple tracking, done consistently, can improve how proposals are planned and evaluated.

Lindsay Keir: The sophistication of the system matters less than having a consistent way to capture and review information. For smaller firms, that might be a spreadsheet or a shared folder structure. As firms grow, more formal tools like CRMs can help track pursuits, hit rates, and client intelligence — but only if teams actually use them consistently.

What’s important is that the firm can look back over time and see patterns. When information is organized and accessible, teams can start to understand what types of pursuits are worth chasing, where effort is being concentrated, and where adjustments might improve outcomes. That kind of visibility supports better prioritization, not just better proposals.

Oomph: And templates play a role in holding all of that together.

Lindsay Keir: They do. Templates establish brand consistency — typography, colours, logo use, margins — so proposals and related materials clearly reflect the firm’s identity. They’re not meant to lock teams into rigid layouts. The goal is continuity and clarity, not uniformity.

CRMs, and “Single Sources of Truth”

Oomph: This naturally leads into systems — where all of that information actually lives. How important is it to have a centralized place for proposal data?

Natasha Basacchi: Having a centralized place for information makes a big difference. Whether it’s a CRM, SharePoint, or another internal system, the goal is to reduce duplication and avoid having the same information scattered across multiple folders and files.

Over time, that becomes a single source of truth — for project data, fees, narratives, and contacts — which makes future proposals more efficient and more accurate. Teams spend less time searching for information or reconciling versions, and more time focusing on the quality of the submission.

Lindsay Keir: The specific tool matters less than having a system that fits the size and complexity of the studio. Smaller firms don’t need enterprise platforms, but they still benefit from capturing and tracking information in one reliable place.

From a continuity standpoint, centralization is critical. When key knowledge lives in a shared system rather than in one person’s head, the work doesn’t stall if someone is away or transitions out of a role. It reduces risk, supports smoother handoffs, and makes the firm more resilient as teams and workloads change.

Managing Sub-Consultants

Oomph: One area where structure becomes especially important is managing sub-consultants. Where do you see things working well — or breaking down — in that process?

Lindsay Keir: From the sub-consultant side, clarity really matters. They’re often being contacted by multiple teams at the same time, so the easier you make it for them to respond, the better the outcome. If you can provide a clear template that shows exactly how information should be delivered — scope, fee, team, availability — you’re far more likely to get usable input.

We’re often reaching out to three or four firms for the same discipline. When one firm takes the time to tailor their response and make it easy to integrate into the proposal, that effort stands out. Sending a generic package or a long PDF with an entire corporate history doesn’t help — it actually creates more work and can influence who we choose to carry forward.

Natasha Basacchi: Templates help on the firm side as well — both for internal tracking and for communicating with consultants. Standard requests, clear deliverables, and consistent contact records reduce back-and-forth and save time.

Tracking who was contacted, what was received, and what’s outstanding makes it much easier to manage multiple consultants on tight schedules and ensures nothing falls through the cracks.

The Bad — Where Procurement and RFP Processes Break Down

Oomph: We’ve talked about what works when systems and processes are in place. I’d like to turn to the other side of that — where procurement and RFP processes make it harder for firms to put forward their best work. From your experience, where do things most often break down?

Lindsay Keir: From a professional practice perspective, risk management sits at the centre of this. In larger firms, there’s often in-house legal counsel. Mid-sized firms may have external counsel on retainer. But smaller firms don’t always have that kind of support — and that’s where things can become risky very quickly.

This is where resources like the Ontario Association of Architects’ practice advisory service are critical. If an RFP raises red flags around liability, scope, or contractual obligations, firms can submit it to the OAA for review. The advisory team provides guidance on what’s reasonable, where risks may exist, and whether the terms align with professional obligations. In cases where an RFP is particularly problematic, the OAA may even contact the issuing organization directly to explain why the document needs to be revised. That kind of support can directly influence whether a firm decides to pursue the work at all.

Natasha Basacchi: On a more practical level, conflicting information within RFPs is a frequent issue. Required deliverables may be listed in one section, but the evaluation criteria don’t align — or new forms and requirements appear later without being referenced earlier. That lack of consistency creates uncertainty and unnecessary guesswork.

Another challenge is when experience requirements become extremely restrictive. In some cases, very specific expertise is genuinely necessary, but in others the criteria are so narrow that capable firms are excluded even when they clearly have the ability to deliver the project.

Fee weighting can also be an indicator. When fees account for a very high percentage of the score, it changes how firms interpret the intent of the process and whether the pursuit is worth the effort — especially when timelines are already tight.

What Realistic Timelines Actually Look Like

Oomph: For public architectural RFPs, timelines are often a pain point. Based on your experience, what’s realistic — both for standard projects and for more complex pursuits?

Natasha Basacchi: Anything under two weeks is unrealistic. For most standard public projects, three to four weeks is much more appropriate. That amount of time allows teams to assemble the right people, coordinate inputs, and respond properly to the requirements.

Lindsay Keir: That timeframe is also important from a risk and quality perspective. It allows for internal coordination, legal and contractual review, and meaningful questions during the Q&A period. Four weeks is a solid baseline for a typical project.

For more complex pursuits, timelines need to be longer. Two to three months is common, and some large federal or infrastructure projects require at least six weeks or more simply to coordinate teams, consultants, and compliance properly.

Natasha Basacchi: Even then, timelines are often extended. Looking at historical data can help clients plan more realistically, rather than assuming extensions will happen by default or that teams can absorb compressed schedules without consequences.

Vendor-of-Record Models and Reducing Proposal Burden

Oomph: In your experience, where do vendor-of-record arrangements work well — and what do they change for proposal teams?

Lindsay Keir: They can make a huge difference, especially in retail and other high-volume environments. Many retail clients already operate this way — you’re appointed to a roster for a defined period, and then individual assignments are scoped and priced as they come up. You’re not re-submitting a full proposal every time for work that’s fundamentally similar.

That approach shifts the focus from constant proposal production to delivery and fees. It also creates a clearer understanding of scope and expectations on both sides. When you’re doing dozens or hundreds of similar projects, that structure saves an enormous amount of time and effort.

Natasha Basacchi: From a proposal perspective, it reduces repetition. Firms often see the same RFP issued again and again with only minor changes, but each time it still requires full tailoring and coordination. Vendor-of-record models reduce that burden and allow teams to focus their energy where it adds the most value.

Lindsay Keir: It also tends to lead to better outcomes for clients. Teams aren’t rushing to produce a full submission under tight timelines for every small assignment. Instead, they can respond more quickly, with clearer pricing and a stronger focus on delivery.

What Separates “Competent” from “Consistently Winning the Right Work”

Oomph: If you step back from all of this — capacity, data, judgment, pre-positioning, leadership, and infrastructure — what’s the core shift firms need to make if they want to move from simply producing proposals to consistently winning the right work?

Lindsay Keir: It comes down to discipline and judgment. Firms that win consistently have clear processes — especially around Go / No-Go — and they actually use them. They understand where they’re competitive, where they’re not, and they’re willing to say no when a pursuit doesn’t align with their strategy or capacity.

That discipline protects teams and focuses effort where there’s real opportunity. Over time, it leads to better outcomes, less burnout, and a much stronger hit rate.

Natasha Basacchi: Data supports that judgment. Even imperfect tracking helps firms make more informed decisions — about where to focus, how to resource pursuits, and when to step back. It reduces wasted effort and allows teams to use their time more strategically.

When firms combine that data with clear leadership decisions and realistic resourcing, proposals stop being reactive and start working as part of a deliberate growth system.