The Cost of Asking Proposals to Carry Growth Alone

In the first article, we looked at why proposals have become the primary engine of growth in architecture, engineering, and construction — and how they function as late-stage sales tools within a much larger system of marketing and demand creation.

This article is the second in a two-part series examining how design firms win work — and the role proposals play within the broader system of marketing and business development. Together, the articles provide context for this month’s interview on proposals and establish a foundation for a broader focus on growth and selling in the months ahead.

In the first article, we looked at where proposals sit within the broader system of marketing and sales — and why, in architecture, engineering, and construction, they have become the primary vehicle for converting opportunity into revenue.

That framing raises a more difficult question: what happens when proposals are asked to do more than they reasonably can?

This is not a question of effort, talent, or commitment. Proposal teams work extraordinarily hard. The issue is structural — and it’s one that decades of marketing research now help us understand with far more clarity than ever before.

WHY PROPOSALS BECOME THE CENTRE OF GRAVITY

In most design firms, proposals sit at the point where business development becomes tangible.

They arrive when a potential project is real, when a budget may exist, and when the outcome feels binary: win or lose. Because of this, proposals draw attention, urgency, and resources. They are also one of the few moments in the growth process where activity can be clearly observed and measured.

This makes them feel like the safest place to invest.

Time spent on proposals can be counted. Win rates can be tracked. Revenue can be attributed. When a proposal succeeds, the link between effort and outcome appears direct and defensible — particularly compared to marketing activity, whose effects are slower, cumulative, and harder to isolate.

As a result, many firms resolve the long-standing marketing versus sales tension by defaulting toward sales activation. Proposal teams grow. Processes become more elaborate. Templates, systems, and workflows multiply. Meanwhile, broader marketing activity remains limited, episodic, or under-resourced.

This response is understandable. But it has consequences.

WHAT OVER-RELIANCE ON PROPOSALS LOOKS LIKE IN PRACTICE

When proposals carry the bulk of growth responsibility, several patterns tend to emerge over time.

Effort becomes episodic rather than cumulative. Teams mobilize intensely for each pursuit, then stand down once a decision is made. Very little carries forward from one bid to the next beyond lessons learned.

Submissions become longer and more complex. In the absence of strong prior familiarity or positioning, proposals attempt to do more explanatory and persuasive work, often expanding to include extensive background, philosophy, credentials, and justification.

Fee pressure increases. Without pre-established credibility or differentiation, proposals are evaluated primarily on compliance and cost, particularly in formal RFP environments.

Teams experience fatigue and burnout. As page counts rise and timelines compress, proposal work becomes increasingly demanding — without a corresponding improvement in outcomes.

These symptoms are often treated as operational problems: not enough time, not enough people, not enough process. But they are better understood as signals of a deeper imbalance.

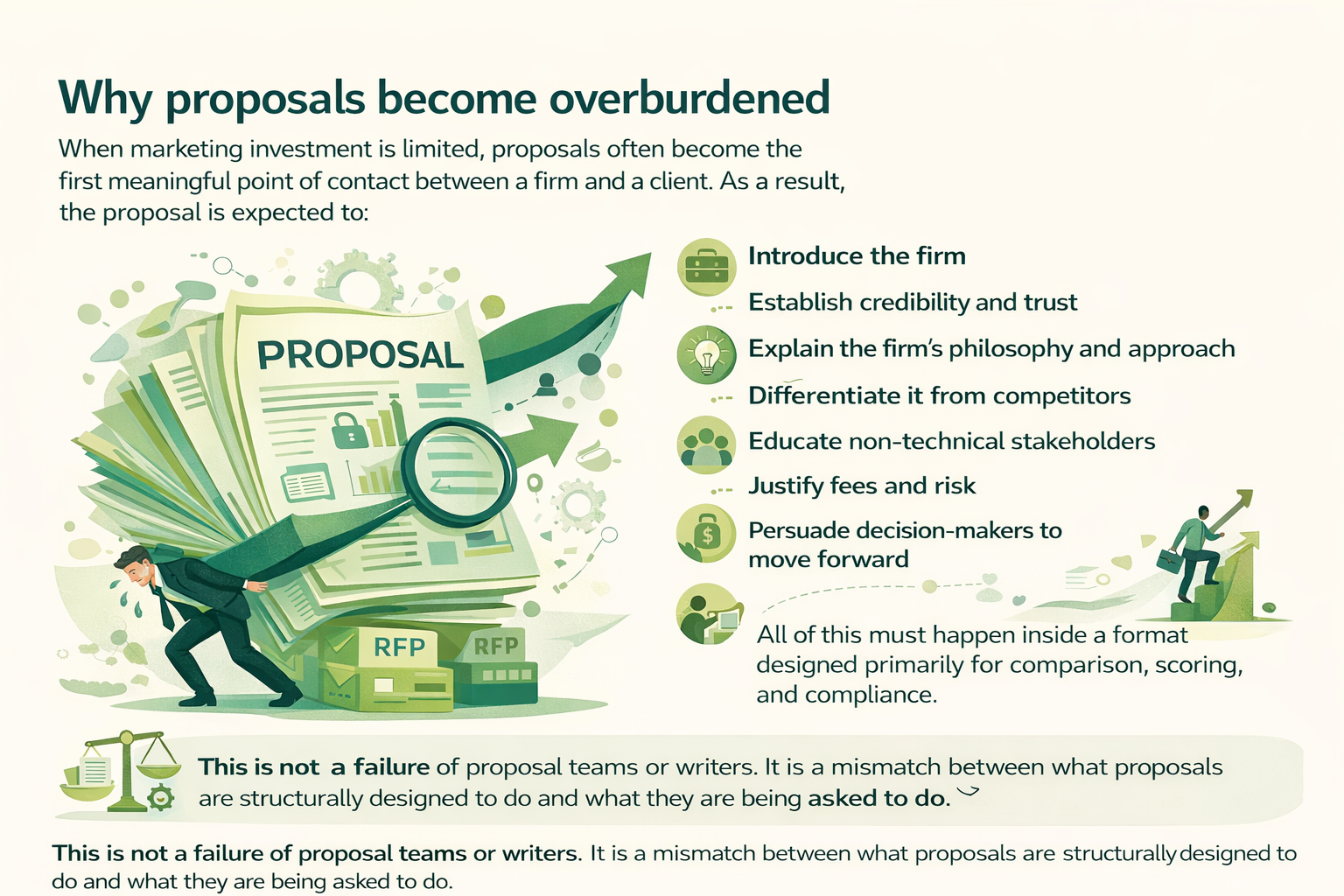

WHY PROPOSALS BECOME OVERBURDENED

When marketing investment is limited, proposals often become the first meaningful point of contact between a firm and a client.

As a result, the proposal is expected to:

introduce the firm

establish credibility and trust

explain the firm’s philosophy and approach

differentiate it from competitors

educate non-technical stakeholders

justify fees and risk

persuade decision-makers to move forward

All of this must happen inside a format designed primarily for comparison, scoring, and compliance.

This is not a failure of proposal teams or writers. It is a mismatch between what proposals are structurally designed to do and what they are being asked to do.

Proposal obesity is a symptom of brand starvation.

WHAT DECADES OF RESEARCH NOW MAKE CLEAR

For many years, these dynamics were discussed largely through anecdote and experience. Marketing leaders argued for the importance of brand building, while sales leaders pointed to immediate results. The debate persisted because hard evidence was limited.

That is no longer the case.

Over more than four decades, organizations such as the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute and the IPA Databank have conducted sustained, rigorous research into how marketing and sales drive business performance. The IPA Databank alone contains thousands of real-world case studies, tracked over long periods and correlated with outcomes including market share, profitability, resilience, and long-term growth.

The findings are consistent and well-established:

Short-term sales activation converts existing demand

Long-term brand building creates future demand

Sales activation draws on brand equity built over time

When brand investment declines, activation becomes less effective and more volatile

In other words, the short term borrows from the long term — until there is nothing left to borrow.

THE 60/40 PRINCIPLE - AND WHY IT MATTERS

By analyzing decades of IPA Databank case studies, researchers Les Binet and Peter Field identified a recurring pattern across categories: the most effective growth strategies balance investment between brand building and sales activation, with roughly 60% allocated to brand and 40% to activation.

This is not a rigid formula. The optimal balance flexes based on category, purchase frequency, risk profile, and market maturity. In complex, high-risk categories — including professional services — the brand component often needs to be stronger, not weaker.

What matters is the principle: firms that over-invest in short-term activation at the expense of brand consistently underperform over time.

Brand investment has been shown to:

increase mental availability

improve pricing power

stabilize performance through downturns

amplify the effectiveness of sales activity

Marketing does not replace sales.

It enables sales to work more reliably and more efficiently.

WHY THIS EVIDENCE MATTERS SO MUCH IN AEC

AEC firms operate in markets where buying cycles are long, purchases are infrequent, and risk is high. At any given moment, only a small proportion of potential clients are actively procuring services. Most are not “in the market” — but they are forming impressions that will shape future decisions.

When marketing is neglected, proposals are forced to create trust and familiarity at the very end of the buying journey, when clients are least receptive to it. The result is more effort, more documentation, and more pressure — without a compounding effect.

This is why firms that rely almost entirely on proposals often find themselves working harder for diminishing returns.

What this means for firms that want to grow

The implication is not to reduce focus on proposals. Proposals remain essential. They always will.

The implication is to rebalance the system around them.

When marketing investment builds sustained visibility, credibility, and distinctiveness:

firms are more likely to be shortlisted

proposals can focus on fit, strategy, and value

sales efforts become more efficient

teams stop starting from zero with every pursuit

This is where dedicated marketing expertise matters — not as proposal support, but as a driver of long-term demand creation and commercial effectiveness.

Proposals work best when they are supported by deliberate, sustained marketing investment — not when they are asked to compensate for its absence.

WHY THIS ARTICLE EXISTS

This is the point at which research, experience, and practice converge.

Firms do not struggle with proposals because they lack effort, talent, or commitment. They struggle when proposals are asked to carry responsibilities that belong earlier in the growth system.

Decades of evidence now show that sustained marketing investment is not optional for firms that want predictable, resilient growth. It is the condition that allows proposals to do what they are designed to do — convert opportunity into work — rather than compensate for everything that came before.

Proposals will always matter.

But they work best when they are supported by a broader system designed to make them credible, focused, and effective.