Proposals Are the Engine — Not the Entire System

This article is the first in a two-part series focused on business development in design firms. Together with this month’s proposal interview, it explores how proposals function as a core sales tool — and why they only work effectively within a broader marketing and demand-creation system. The series continues next month with a focus on websites as the second critical sales vehicle for design practices.

WHAT HAS TO BE IN PLACE FOR PROPOSALS TO WIN

In architecture, engineering, and construction, proposals are the primary vehicle for procuring work.

They are how firms convert opportunities into revenue. They determine whether a lead becomes a project, whether effort turns into income, and whether months of relationship-building result in a signed contract.

Because of that, proposals attract disproportionate attention and investment. They shape how firms organize their teams, where they allocate marketing and business development budgets, and what skills they prioritize when hiring. In many firms, the first — and sometimes only — marketing hire is a “marketing coordinator,” a role defined less by strategy or demand generation than by one essential capability: proposal production.

As a result, proposals often absorb the bulk of a firm’s marketing and business development resources — time, talent, leadership focus, and budget. They become the most visible expression of growth activity, the place where effort is easiest to justify and outcomes feel most measurable.

For many firms, proposals aren’t just part of the growth process. They are the growth process.

But proposals don’t operate on their own. They sit inside a much larger system of how firms build credibility, create demand, and earn trust over time. To understand why proposals succeed — or why they struggle under increasing pressure — we need to step back and examine the broader relationship between marketing and sales, and why this tension exists in virtually every industry.

THE OLDEST BUSINESS TENSION: MARKETING VS. SALES

Every company that sells anything — products or services, physical goods or professional expertise — grapples with the same fundamental question: what actually drives growth?

In most organizations, marketing and sales evolved as distinct functions. They are often led by different people, funded through different budgets, and measured in different ways. In mass-market companies, this divide is easy to see. Sales is responsible for distribution, channels, transactions, and revenue. Marketing focuses on advertising, brand visibility, campaigns, and events — work that shapes perception rather than closes a deal directly.

The same dynamic exists in professional services, including architecture, engineering, and construction — just in a different form. Many design firms have marketing teams, but in practice those teams are largely dedicated to proposal production. Outside of maintaining a website, producing project photography, or publishing the occasional case study or social post, broader marketing activity is often minimal. Most effort, time, and resources are directed toward bids and pursuits tied to specific opportunities.

This isn’t a failure of intent. It reflects a structural tension that exists wherever organizations must choose between long-term influence and short-term results.

WHY THIS TENSION EXISTS EVERYWHERE: MEASUREMENT AND TIME

At the heart of the marketing-versus-sales debate is measurement.

Sales activity is discrete and attributable. A team works on a proposal for two weeks. The proposal is submitted. The project is won. Revenue follows. The relationship between effort and outcome feels clear, defensible, and easy to explain.

Marketing works differently. Activities such as thought leadership, public relations, speaking, content, and visibility build familiarity and credibility over time. Their effects accumulate gradually, often influencing decisions months or years later alongside many other factors. Rarely can they be tied to a single transaction.

Because of this asymmetry, organizations naturally gravitate toward what can be counted. Over the past two decades, this has fuelled the rise of performance marketing, attribution models, and short-term activation tactics designed to demonstrate immediate return. This shift didn’t happen because long-term marketing stopped working. It happened because short-term activity is easier to measure.

That instinct is rational — but it comes with consequences.

FROM BELIEF TO EVIDENCE: WHAT MARKETING RESEARCH HAS CHANGED

For much of its history, marketing relied on experience, intuition, and anecdote to explain its value. Marketers knew brand mattered, but struggled to prove how and why. That has changed.

Over the past 40 years, marketing has matured into a rigorous research discipline. Institutions such as the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute and the IPA Databank have analysed thousands of campaigns across industries and economic cycles, tracking performance over time. Their work has reshaped our understanding of how demand is created and sustained.

The evidence consistently shows that long-term brand building increases mental availability — the likelihood that a firm comes to mind when a buying situation arises. It also shows that brand investment strengthens sales activation, improves resilience during downturns, and reduces price sensitivity over time.

Marketing does not replace sales. It makes sales more effective.

WHY THIS MATTERS MORE IN AEC this matters more in AEC

These dynamics are especially pronounced in architecture, engineering, and construction.

AEC firms sell complex, high-risk services with large dollar values and long timelines. Buying cycles are rarely short. Decisions are made by committees, not individuals. Clients often begin evaluating firms long before a formal RFP is issued — sometimes years before a project exists at all.

In this context, marketing plays an upstream role. It builds familiarity, credibility, and confidence long before a proposal is written. It creates the conditions that make a firm feel like a safe, credible choice when the moment to buy finally arrives.

Proposals operate at a different stage. They are project-specific sales tools designed to move a known opportunity forward. Their job is to confirm fit, frame value, reduce perceived risk, and help decision-makers say yes to a specific engagement at a specific moment.

A proposal is a selling document designed to move a specific opportunity forward — not a brochure.

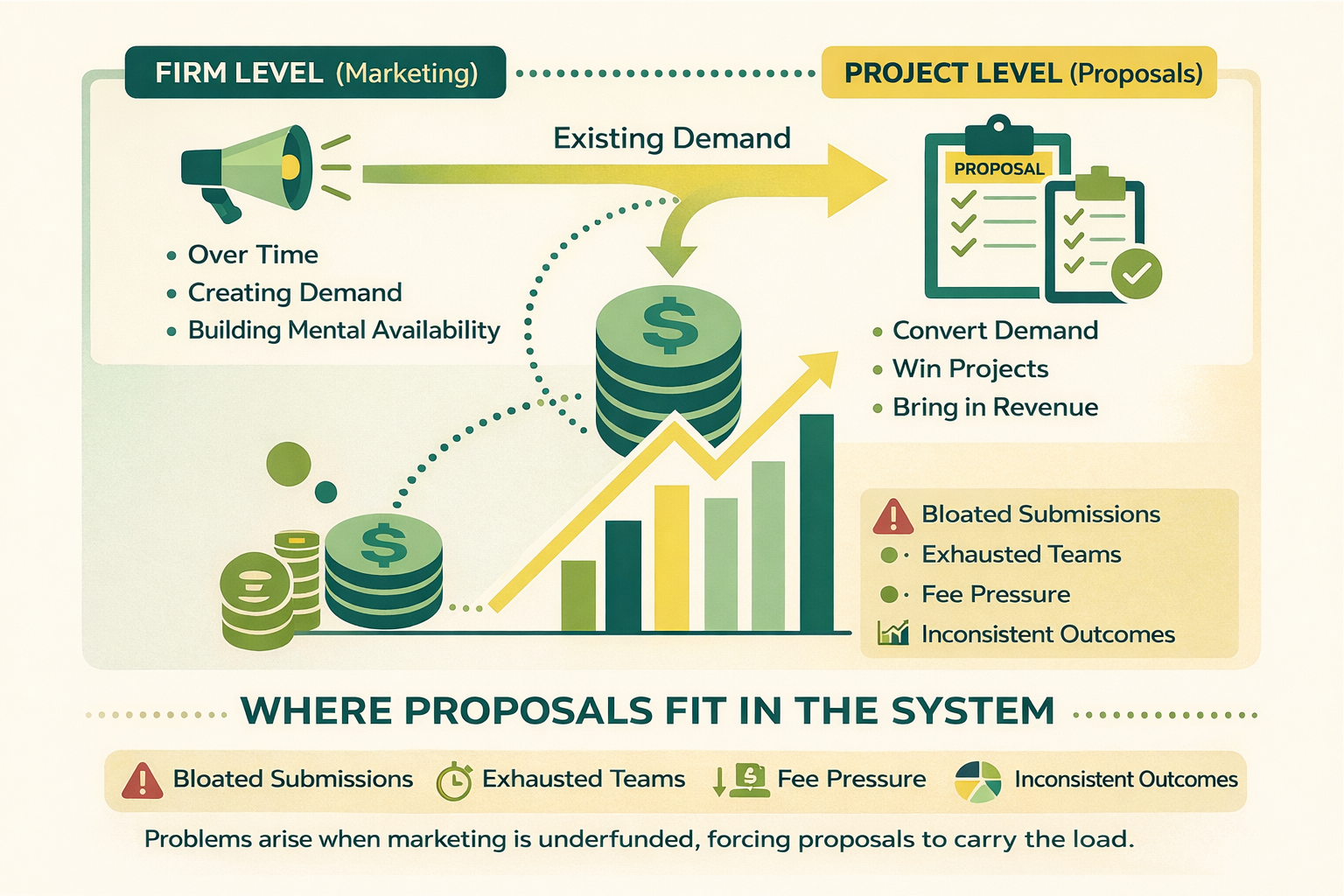

WHERE PROPOSALS FIT IN THE SYSTEM

Seen this way, the distinction is clear. Marketing works at the firm level, over time, creating demand and mental availability. Proposals work at the project level, converting existing demand into revenue.

Problems arise when this distinction collapses — when proposals are expected to carry the work of marketing as well as sales. When firms underinvest in marketing, proposals are forced to introduce the firm, explain its philosophy, differentiate its approach, prove competence, reassure non-technical stakeholders, and justify fees — all inside formats designed for compliance and comparison.

Understanding this system matters. When proposals are asked to do everything, strain shows up quickly: bloated submissions, exhausted teams, fee pressure, and inconsistent outcomes. That’s where the real cost of imbalance begins to surface — and where the evidence becomes impossible to ignore.